Our History Blog

With Hope for Lasting Peace: Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the End of World War II

By Taylor Barnett, University Archives and Special Collections Intern

My name is Taylor Barnett, and I am a junior history major here at Xavier. I helped to co-curate an exhibit commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II as the University Archives and Special Collections intern, a position which I obtained to learn about archival work and practice the skills that I have learned in my humanities internship course. In this course, I have outlined clear goals for myself and my work including learning general information about archival work, workplace skills and behaviors, and paying attention to lessons learned from my projects at my internship.

This exhibit explores the effects of World War II on Xavier University. When the United States entered World War II, the University’s enrollment dwindled as male students entered military service either through enlistment or the draft. To save the University, Father Steiner, S.J., signed a contract with the federal government to allow the 30th College Training Detachment to train and study at Xavier. Without such an agreement, Xavier’s doors would have closed due to low enrollment. The exhibit shares artifacts and stories documenting the experiences of former Xavier students and the 30th College Training Detachment in the war. It also highlights the impact of the GI Bill and changing workforce needs on Xavier and its curriculum.

Members of the 30th College Training Detachment march along University Drive in 1943. Photo from the Xavier University Photograph Collection.

By researching the individuals featured in this exhibit and finding ways to present this information, I have discovered how difficult it may be to locate and display information. Archivists try to preserve documents’ original contexts as much as possible, however, others looking at documents have copied down names or places incorrectly, leading to some repeated errors. Simply researching became much more time-consuming than I originally thought, as did the actual curation of the exhibit. When the time came to choose the veterans’ portraits, I discovered the difficulty in working with several types of media. Scanning from newspapers, for instance, created a grainy texture for photographs that does not reprint well. I then had to mount, frame, measure, and finally place a number of labels and items on display, and this allowed me to experience the creative and physical work required to become an archivist in addition to research and organization skills. Most importantly, however, I appreciated the collaborative effort involved in curating even a smaller exhibit such as this one. Anne Ryckbost, University Archivist, and I drafted, revised, and reviewed each label multiple times, another time-consuming yet very important part of archival work.

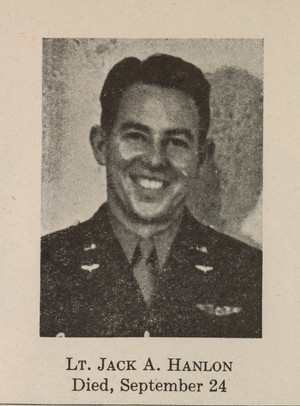

Lt. Jack A. Hanlon withdrew from Xavier in 1942 to enlist in the U.S. Army. He was killed in a plane crash on Sept. 24, 1944. Photo from the Xavier Newsletter.

As I conducted my research on Xavier and World War II, I discovered so much about the campus near which I have always lived. I realized the extent to which I encounter local history without realizing it every day. For example, the Shrine of Our Lady, Queen of Victory and Peace is a statue which I pass nearly every day, but it was not until I began my research that I discovered its importance. Built in 1943, this memorial honors Xavier students who gave their lives in the service of the military. Also, Elet Hall, the building in which I attended classes for several semesters, was the dormitory of hundreds of trainees of the 30th College Training Detachment which saved Xavier’s enrollment and prevented the university’s closure. Without those trainees, I would not have had the opportunity to co-curate this exhibit today. My favorite historical lessons from this project, however, were those that I learned about the veterans memorialized here. Getting to know these former Xavier students has helped me to feel closer to campus and our community as a whole.

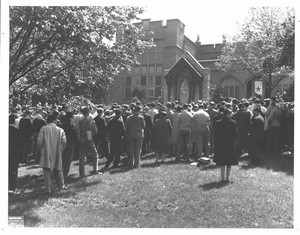

Xavier students, faculty, staff and community members pray at the Shrine of Our Lady, Queen of Victory and Peace on V-E Day, May 8, 1945. Photo by Marsh Studio, from the Xavier University Photograph Collection.

The Twists and Turns of Our Constitutional Amendment

By Nick Watts, Constitution Day Fellow

Project: John Boehner and the 27th Amendment

My name is Nick Watts and I am a sophomore PPP and history double major. Unsurprisingly, I will soon be picking up Xavier’s new constitutional studies minor! Even more unsurprisingly, I love history, politics, and research. When I am able to combine all three, it becomes even more fun. Although the research can be detail-heavy at times, I am thankful that the necessary documents relevant to this project are all printed in legible English! That is more than I can say for past archival research I’ve done where it can take hours to half-decipher a single sentence.

I approached this project as the exciting opportunity that it has been to be one of the first Xavier students to delve into the John Boehner Papers. Going in, I didn’t know much about the substance or relevance of the passage of our most recent constitutional amendment. Looking back, I now have not only an appreciation for number 27 itself but for the entire amendment ratification process. Although difficult, I had no idea how truly herculean of a task it is to try to amend the U.S. Constitution. Leaving with a newfound appreciation for history is one of the things that a research project gives that can’t come from anywhere else. Spending weeks studying the intricacies of a specific concept helps build connections between larger ideas. Two previous major research projects I did on the 1862 Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico and the 62nd Governor of Ohio John J. Gilligan’s passage of an income tax in Ohio brought me the same gratification. It was nice to return to this feeling.

Archivist Anne Ryckbost does an incredible job curating Xavier’s history and preserving such an impressive collection as former Speaker John Boehner’s. I wouldn’t have been able to get anywhere on this project without her and I look forward to returning to the University Archives and Special Collections for future projects to discover what other connections to national history Xavier’s past offers.

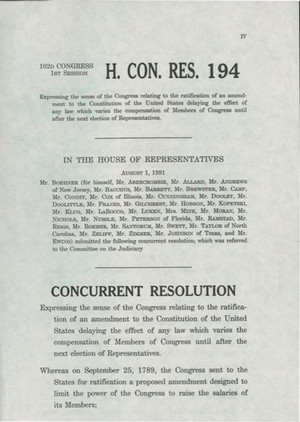

Con. Res. 194, Box 4, Folder 14, MS-009 John Boehner Papers, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

John Boehner speaking at Xavier University Commencement, May 14, 2016, Xavier University Photographs, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

John Boehner speaking at Xavier University Commencement, May 14, 2016, Xavier University Photographs, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

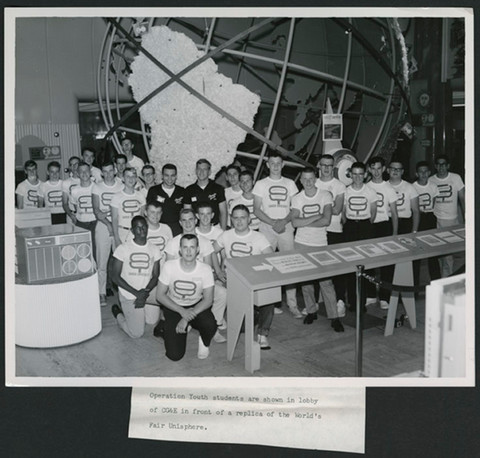

Operation Youth: A Legacy of Leadership and Civic Education

Constitution Day Fellow Savannah Hugenberg researched the Operation Youth program hosted by Xavier University from 1950 until 2001. Savannah is a Sophomore PPP major with a minors in psychology and economics.

Operation Youth was once a hallmark of civic education at Xavier University. This one-week summer program, initially launched in 1950, brought high school juniors and seniors together to cultivate leadership, democracy, and a deep understanding of their civic responsibilities. By offering students the chance to experience the tenets of American democracy firsthand, the program left an indelible mark on the thousands of young men, and eventually women, who passed through campus.

Historical Overview of Operation Youth

In its early years, Operation Youth combined academics, discussions on American values, and hands-on civic activities to instill democratic principles in high school boys. The program featured lectures, field trips, and observations of American institutions, all aimed at fostering civic engagement. Ultimately, the program opened its admission to women, reflecting its growth with the modernization of American culture.

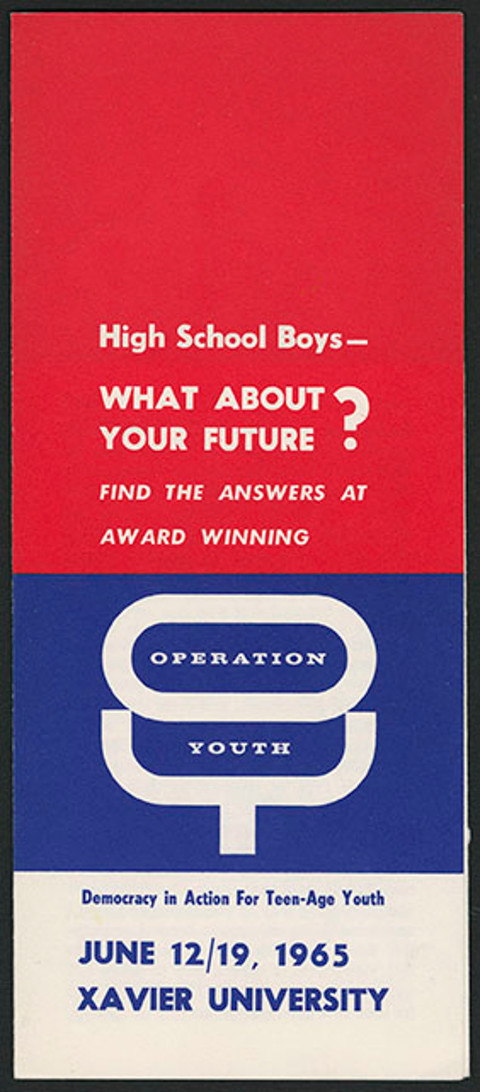

The brochure for the 16th annual Operation Youth, held in 1965, provides a snapshot of the typical experience. Delegates participated in flag-raising ceremonies, attended lectures on Americanism, and engaged in discussions about democratic values and governance. The day was tightly scheduled to include a combination of assemblies, guided tours of local industries, and recreation, ensuring that the students were exposed to different aspects of American society. This gave opportunities for the young students to network, meet peers from different backgrounds, and share ideas. Operation Youth’s curriculum also incorporated discussions on family life, economics, and the relationship between business and democracy—recognizing the importance of these factors in maintaining a free society.

A Personal Reflection from Michele Watts (Speath)

Michele Watts (Speath), who participated in Operation Youth in 1985 and became a senior leader in 1988, describes the experience as one of the most impactful of her life. "It wasn’t just about politics—it was about building relationships and understanding American freedoms," she says. The program, led by the disciplined Bill Smith (Smitty), was structured and rigorous, yet it created a space for genuine connection. Michele recalls, "It felt like a retreat, where we not only learned about government but also shared personal stories. For many of us, it was the first time we felt comfortable being vulnerable."

Civic Education and Leadership Development Today

Operation Youth was more than just a summer program—it was a space for young leadership, offering invaluable experience in civic education and personal growth. The personal stories of alumni like Michele Watts (Speath) remind us that the program wasn’t only about the subjects discussed or the structure of the days. It was about forging connections and deepening an understanding of what it means to be a part of a democratic society. Though the program may not be active, the legacy of Operation Youth lives on in the lives of those who participated, who continue to live out its ideals of leadership, community, and civic engagement.

Operation Youth Brochure, 1965, Box 1, Folder 1, XUA-144 Xavier University Collection of Operation Youth Records, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Operation Youth Participants, 2001, Box 1, XUA-148 William E. Smith Operation Youth Records, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Participants visit Cincinnati Gas & Electric, Box 1, Folder 5, XUA-144 Xavier University Collection of Operation Youth Records, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

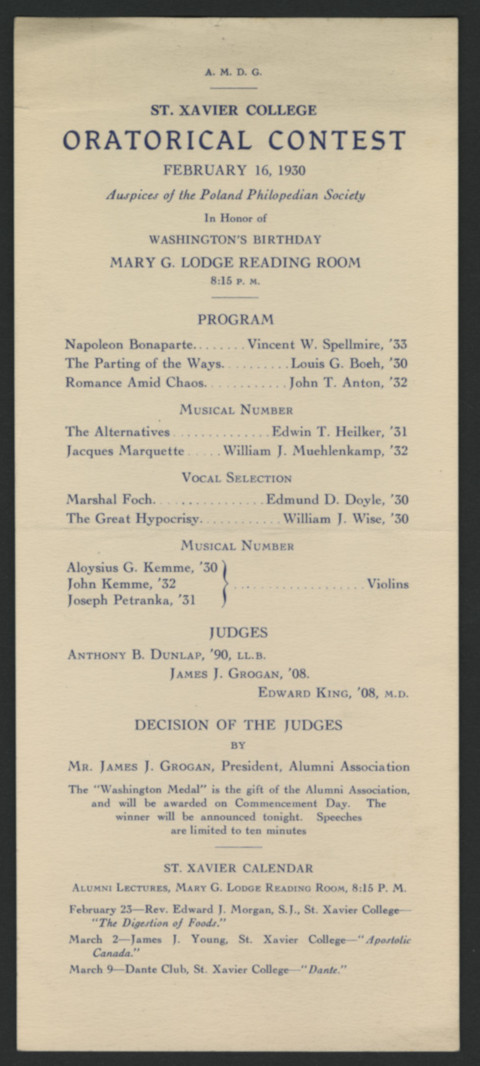

George Washington Birthday Commemoration

In fall 2024, Xavier student Ethan Pilote conducted research on the annual George Washington Birthday Commemoration hosted by Xavier University in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Reflecting on the history of the celebration, Pilote writes, “Beginning in 1841, the spring following the Jesuit’s assumption of the Athenaeum, the celebration of George Washington’s birthday became an annual event. George Washington was an idol within the college due to the general understanding that he was a noble American leader, known to express patriotism, and had a strong sense of civic duty. The mission behind this celebration was to push students to pursue an issue relating to the United States, promoting students to take action in society. In the early years, it was mandatory for every student to participate in or attend the commemoration featuring a contest of speeches made in honor of Washington, but as it and the school grew that was no longer an option. The majority of the early planning was done by the Philopedian Society, which met frequently throughout the year to debate current events. In 1893 the Alumni Association took hold of the event and officially introduced the Gold Medal, also known as the Washington Medal, which was gifted to the winner upon commencement. The event was held often in Memorial Hall on campus but, as popularity grew other venues would be available. In the year 1911, the celebration occurred at the Grand Hotel in Cincinnati where over 100 guests were reported.

St. Xavier College Oratorical Contest program, February 16, 1930, XUA-106 Box 6, Folder 3, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Students (William Roll and Bernard Gilday) debate in Conaton Board Room, February 21, 1941, XUA-125 Xavier University Photographic Negative Collection, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Describing Xavier's Photographic Past

By Molly Linkous, Office of the Registrar Staff and University Archives and Special Collections Intern, March 2024, with support from University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

My name is Molly Linkous, and I am currently interning for University Archives and Special Collections while I complete the final semester of my Master’s in Library and Information Sciences at IUPUI. I also happen to work in Xavier’s Office of the Registrar. My primary project with University Archives has been creating titles and descriptions for 756 images in the Xavier University Photographic Negative Collection as part of the workflow to share them online in Exhibit, the institution’s digital repository. Many of the originals in this collection were nitrate and acetate negatives, which pose significant preservation challenges. In 2007, University Archives contracted with the Northeast Document Conservation Center to digitize all the negatives. While the digital files were retained, the originals were destroyed after the project due to their fragility and preservation risks. During this digitization process, whatever information was recorded on the envelope that housed the original negatives was documented, but these identifications were often sparse. Many of the negatives were also found loose, so no such markings or notes were available for those.

These image descriptions contribute to the creation of image metadata. Metadata is data about data, and includes information like title, date, location, and keywords. Metadata provides a structured reference point to label the characteristics of an object or file. A clear, detailed description can make these images accessible, organized, and searchable. Metadata helps provide identification and context for current and future generations.

The process of creating descriptions varies depending on the level of previous information available for the images, the significance of the image, and its contents. I use digitized yearbooks and student newspapers as my primary research tools. Especially when a date is recorded for an image, I will first turn to yearbooks. If an image is loose, I will use image content like clothing, activities, or people, to narrow down possible time frames and subjects. Sometimes I recognize a person or the image itself from my previous research.

This image was a loose image, meaning it had no envelope noting its original date or subject matter. I could tell it was a group of adult men, not students, which narrowed down the types of organizations or events it could have been from. Luckily, this image is quite distinct and leaves an impression, and I recognized it. There had been only a handful of yearbooks that I had recently searched through, so I went back through all of them, focusing on the adult groups like the Faculty, Alumni, and the Dads’ Club. Sure enough, there it was on the Dads’ Club yearbook page in 1941, along with a short caption. The image shows a “Group of Freshmen dads being initiated into the Dads' Club.” While the original negative is undated, it was likely captured around 1940 or 1941 because it appears in the 1941 yearbook.

Since time and resources are limited, not all images receive this in-depth research for their description. Still, it’s gratifying when I can put the pieces of the puzzle together and share the information.

“Freshmen dads initiated,” 1941, XUA125-n00271, XUA-125 Xavier University Photographic Negative Collection, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Musketeer, 1941, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Musketeer, 1941, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

How St. Xavier College Became Xavier University: 1919 to 1930

By Thomas Kennealy, SJ, August 2023, with support from University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

During its almost 200-year history, Xavier University has had three names. When the University was first established in 1831, its founder, Bishop Edward Fenwick, O.P., called it the Athenaeum. When the Jesuits arrived and took over in 1840, they changed the name to St. Xavier College. In 1930, the institution became Xavier University.

Construction on Bishop Fenwick’s new college in the diocese of Cincinnati, Ohio started in 1829 and finished in 1831. The college was located on the west side of Sycamore Street between Sixth and Seventh Streets in downtown Cincinnati. The phrase “Athenaeum: Religioni et Artibus Sacrum,” (the Athenaeum Dedicated to Religion and the Arts) was inscribed above the main entrance. This motto summarized the goals of the college: the promotion of religion and the education of the young in the liberal arts.

By 1839, it was clear to Fenwick’s successor, Bishop John Baptist Purcell, that the college was facing serious problems which required immediate attention if the school was to survive. Bishop Purcell decided to offer the college to the Society of Jesus, a religious order of men popularly known as the Jesuits, one of whose primary apostolates was establishing and operating Catholics colleges. On September 30, 1840, eight Jesuits led by Father John Elet, the former president of St. Louis University, left Missouri for Cincinnati. On November 3, the college opened its doors as a Jesuit institution. The Jesuits changed the school’s name to St. Xavier College in honor of St. Francis Xavier, one of the early companions of St. Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, and a famous missionary.

Discussions about changing the name of St. Xavier College began as early as 1919, after the college had relocated from downtown to its current Avondale property. Should the college become a university, a title that a number of American colleges, even Jesuit institutions, were assuming? Should the name “Xavier” be abandoned? Many found it difficult to spell and even more mispronounced it.

At first, the administrations of both the Jesuit order and the college were cool to the idea of changing the name. The Superior of the Missouri Province, to which St. Xavier belonged, was opposed to changing from college to university. In 1919, he wrote to Xavier president Father James McCabe, stating his opinion, “St. Xavier’s is making a fine start towards a university, but I feel that we should not burden it with too big a name. Let me know what you feel in the matter.” Father McCabe replied that he, too, was opposed to Xavier becoming a university.

However, not everyone agreed. At its meeting on January 11, 1922, the St. Xavier Alumni Association adopted the following resolution and sent it to Father. McCabe:

“Be it resolved by the St. Xavier Alumni Association that it is the sense of this body that the matter of change of name of St. Xavier College be suggested to the authorities for consideration and action at some appropriate future time, and that a copy of this resolution be transmitted to the Reverend Rector of the College.”

As the debate continued, many names were proposed. One was Newman University after John Henry Cardinal Newman, the well-known English writer and theologian. Another was Gibbons University in honor of James Cardinal Gibbons, the former Archbishop of Baltimore, and a third name was Bellarmine University after Robert Cardinal Bellarmine, the noted Jesuit theologian. An alumnus wrote to Father Brockman with the following comment: “Any name is apt to sound poorly until one gets accustomed to it. One name that occurred to me was the University of Southern Ohio.”

By early 1930, the administration of the college, including its Board of Trustees, was convinced that a name change was urgent. Accordingly, in May 1930, Father Brockman submitted to the Jesuit superior of the Chicago Province and the superior general of the order in Rome a request to change the school’s name from St. Xavier College to Xavier University. In his petition, Father Brockman sighted ten reasons for the new name. He pointed out that St. Xavier College had added a number of new departments, programs, and colleges, which gave it both the structure and dimensions of a university in the American model. His major reason, however, was the urgent appeals from many quarters. After expressing the displeasure of alumni and benefactors in the lack of a name change, he noted that many graduates confessed to being ashamed of the fact that their alma mater was just a college and not a university.

Rome’s reply arrived on June 4, 1930. The Jesuit Superior General approved the name change on the condition that the Archbishop of Cincinnati, John T. McNicholas, O.P., grant his approval in writing. The following month the Archbishop gave his written permission.

At a meeting on July 31, 1930, the Board of Trustees unanimously approved an amendment to the Articles of St. Xavier College changing the institution’s name to Xavier University. The following day, Father Brockman sent a certification of the amendment to the Ohio Secretary of State and the Department of Education of Ohio requesting their formal recognition and approval. By an act of the Ohio Board of Education on August 4, 1930, St. Xavier College became Xavier University.

Letter from the provincial of the Midwest Province of the Society of Jesus to Xavier’s president from Box 1, Folder 5, XUA-124 Xavier University Collection of Governance Records, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library.