The Service of Faith in a Religiously Pluralistic World

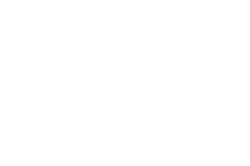

Keynote address by the Very Reverend Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J.,

Former Superior General of the Society of Jesus

October 3, 2006 @ Xavier University

It gives me great pleasure to be with you today during this year of 2006 as we celebrate the 500th anniversary of the birth of St. Francis Xavier, the great missionary of the 16th century for whom your university is named. I am also happy to be with you as you celebrate the 175th anniversary of the founding of your university. Along with Georgetown University, Saint Louis University, and Spring Hill College, your school is one of the senior leaders of Jesuit higher education in the United States of America. The first bishop of the Roman Catholic diocese of Cincinnati, Edward Fenwick, saw the need in his young church for what we know as higher education and founded the Athenaeum in 1831. His successor, Bishop John Baptist Purcell, persuaded the Jesuits to take over the running of the Athenaeum in 1840 when it was renamed St. Xavier College.

From these beginnings, this complex and highly respected institution has grown and matured to become a vital voice in Catholic and Jesuit higher education in the United States. In the name of the Society of Jesus, I thank you for all you have done and continue to do in this important even crucial apostolate of Jesuit higher education. I understand that a new book, tracing the proud history of your school, has just been published. Congratulations.

Your 175th anniversary offers an excellent opportunity to consider the identity and mission of Xavier University, especially in the light of its relationship to the Church and the Society of Jesus; for throughout its history, Xavier has remained faithful to the inspiration of its founders by seeking to serve the Church through the mission of the Society of Jesus.

My words today will concentrate of Xavier's commitment to the religious dimension of the whole person. I do this in order to stress the importance of conversation about religious subjects in all the areas of human existence. In a world in which specialization is increasingly more important, a world in which people learn more and more about less and less until they know everything there is about nothing at all, it is important to remember that religion and religious topics are not just the responsibility of specialized areas like the theology department or campus ministry. Rather, they are the responsibility of everyone at a university. Indeed, everyone involved in Xavier's enterprise has unique contributions and responsibilities regarding this central facet of human existence. In recent addresses on Jesuit higher education in the United States, I have spoken about the service of faith with special attention to the promotion of justice. Today I will speak about the service of faith with particular attention to other religious traditions as it takes place in a particular culture.

Xavier University's fidelity to and participation in the ongoing development of the Church and the Society of Jesus is quite obvious even in the most cursory examination of the past 35 years. In 1971, the Synod of Bishops boldly proclaimed that

"education demands a renewal of heart, a renewal based on the recognition of sin in its individual and social manifestations. It will also inculcate a truly and entirely human way of life in justice, love and simplicity. It will likewise awaken a critical sense, which will lead us to reflect on the society in which we live and on its values; it will make people ready to renounce these values when they cease to promote justice for all people".

In responding to the Church's vision articulated by the bishops, the Society of Jesus developed a similar emphasis in the documents of its Thirty-second General Congregation in 1975. In particular, Decree Four, Our Mission Today: The Service of Faith and the Promotion of Justice, captured both imaginations and attention. In the years since 1975, this conviction about the relationship between faith and justice has been developed and nuanced, debated and challenged.

Justice, like charity, is a word that can easily be misunderstood. Some might say that justice is only about social action or legislation and that charity refers only to almsgiving. However, Pope John Paul II pointed out that the justice of the Kingdom is the concrete, committed way to live out the new commandment of the Gospel, and Pope Benedict XVI restored to charity the full diving and human meaning of love. Both popes have stressed that there will be no justice without Christ's love lived out by all of us; at the same time love will remain only a lovely word if it does not become concrete in deeds of charity and social assistance, of solidarity, and of justice.

In 1995, the Jesuit's most recent General Congregation addressed the relationship between justice and faith, both to emphasize its significance once again and to clarify its meaning. The Congregation stated that the mission of the Society of Jesus and its ministries, such as Xavier University, is the service of faith of which the promotion of justice is an absolute requirement. The integrating principle of this mission is the link between faith and the promotion of the justice of God's reign. Developing this line of thinking even more, the Congregation stressed that an effective presentation of the Gospel must include dialogue with members of other religious traditions and engagement with culture.

Taking into consideration these documents of the Church and Society of Jesus, a few years ago your faculty stated the university's purpose this way: Xavier's mission is to educate, to help develop a deeply human person, one of integrity, wholeness, and dedication, one equipped with values, knowledge and skills related to the whole experience of living. Xavier's mission has also been expressed this way: to educate students intellectually, morally and spiritually, with rigor and compassion, toward lives of solidarity and service.

Before going on, it might be helpful to note why an explicitly religious institution like the Society of Jesus is so interested in education. St. Ignatius and his companions expressed very simply the mission of the religious community they founded: to help souls. The first Jesuits expanded this simple concept as they expressed their basic purpose in this way: the propagation of the faith and the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine. In his book, The First Jesuits, Father John O'Malley helps us understand the meaning and significance of the purpose and of Ignatius's simple expression to help souls. Ignatius and his followers used the phrase as the best and most succinct description of what they were trying to do. By soul Jesuits mean the whole person [T]he Jesuits primarily wanted to help the person achieve an even better relationship with God. Today, of course, we would use other words, just as your faculty did in describing Xavier University's mission; however, the reality is the same: to help develop a deeper human person, one of integrity, wholeness and dedication.

Although education was not part of Ignatius's original vision, it soon became a central facet of Jesuit life. Jesuits recognize that the best way to help people achieve a better relationship with God was by helping them understand their place in the world that God created. Through education, Jesuits sought to introduce students to the even greater glory of God that is revealed as one came to know more and more about the universe and grasps the concepts and ideas that help us organize our understanding of, our place in, and our responsibility to all facets of creation. In 1586, the early educational theorist, Father Diego Ledesma, referred to the purpose of Jesuit schools this way:

Whether they endeavor to teach the laws and form of government conducive to the public good; to contribute to the development, brilliance and perfection of the human mind; and, what is more important, to teach, defend and spread the faith in God and religious practice, they should always and everywhere help people toward the easier and full attainment of their ultimate end.

Xavier University shares in this long and rich heritage. Indeed, you have been helping souls in this tradition for 175 years!

As one might expect, then, there is an obvious connection, between the teaching of the Church, the mission of the Society of Jesus, and Xavier University's self-understanding. Your mission statements express well the truth that effective education is about formation of the while person. True education, education really worthy of the name, is an organized effort to help people use their hearts, heads and hands to contribute to the well-being of all human society. Genuine education helps individuals develop their talents so they may become agents who act with others to make God's liberating and transforming love operative in the world.

Your statement on general education is an contemporary expression of the early Jesuits' commitment to

humanist education. Your continuing commitment to an extensive core curriculum is clearly one way to achieve the goal of understanding the world and one's place in that world. Your emphasis on academic service learning and the continuing attempts to renew and strengthen your Ethics/Religion and Society focus make important contributions to that process. However, it is important for us to recognize that your faculty's words apply to the activity of the entire university, faculty, staff, students, trustees. For all the functions of the university contribute to its mission of educating the whole person.

There are no neutral sciences, no pure academic disciplines that develop isolated from human problems in an ivory tower. Every branch of human knowledge raises questions today about meaning, ethical behavior and more responsibilities. As its very name university confirms, the whole university is involved in the process of educating the whole human being.

Many of your students are at an age when they may be seriously searching for insight into faith and religion, perhaps questioning, doubting, rejecting. In educating the whole person, many different disciplines and facets of university life assist students as they search for meaning, offering light for the process of more deeply understanding what one believes about life's most profound questions such as who am I and why am I here. In fact, many students come to a Jesuit, Catholic university like Xavier because they expect to be helped to grapple with questions of faith in explicitly Jesuit and Catholic ways because of the university's tradition and because of the public image it presents.

Some of your students may identify themselves as members of a religious tradition without actually understanding or appreciating that tradition. How can you help them in a situation like that, especially if religious faith is sometimes seen as a uniquely private affair that has no place in public discourse or is seen at other times as something too important to be left unregulated by a culture's controls? How can you responsibly serve the faith in order to help them?

First of all, most clearly and obviously you do this by doing the work you have come here to do, by being the best you can be at what you were hired to do, by accomplishing the vocation you have received through the unique combination of talents, training and experience that qualify you to work at a place like Xavier. You help students the most by being dedicated teachers, by contributing to the growing deposit of knowledge about the universe and its operations, by serving the broader community in which the university exists. Whether through direct contact with students as professors or through all the supporting services that made education possible, each person at Xavier can pass on what we know about human existence, contribute to understanding more about the universe in which we live, and serve the local community. You help students learn about their faith by faithfully expressing your own faith through the deeds of your lives.

On another level, you can help students learn about their faith by helping them understand as clearly and as profoundly as possible their own religious tradition and by assisting them to find ways to nurture their commitment to this tradition. As a Jesuit, Catholic university, Xavier has particular responsibility to focus on Christianity, with special attention on Roman Catholicism. However, as Xavier attracts students of other religious traditions, it must explore ways to help them too, not only in academic courses but also in support from student services and campus ministry. As even the most cursory examination of a newspaper reminds us, this topic is essential for the health and safety of our world.

The profound vision of human solidarity articulated at the Second Vatican Council is a good place for understanding both this instinct for helping others and for seeing how it can be done:

One is the community of all peoples, one their origin, for God made the while human race to live over the face of the earth. One also is their final goal, God. God's providence, manifestations of goodness, and saving design extend to all people, until that time when the elect will be united in the Holy City, the city ablaze with the glory of God, where the nations will walk in God's light.

The Council continues:

[T]he Church therefore exhorts her sons and daughters, that through dialogue and collaboration with the followers of other religions, carried out with prudence and love and in witness to the Christian faith and life, they recognize, preserve and promote the good things, spiritual and moral, as well as socio-cultural values found among these people.

Following immediately in the inspiration of Vatican II, Xavier University embraced this teaching of the Council regarding other religions, Your Jesuit Father Edward Brueggeman collaborated with ministers of other Christian denominations and with Jewish leaders to found the popular TV series Dialogue, which for years led the people of Greater Cincinnati in mutual understanding. In the years since, that effort of Father Brueggeman has led to the establishment of a chair for inter-religious dialogue and now the establishment of the Brueggeman Center for Dialogue. You have a great deal here for which to be proud.

You have come to understand, however, that dialogue has its own challenges, not immediately apparent to us at first. We can begin our journey of true dialogue by listening to one another in our various religious traditions. We can learn about one another's traditions. But true dialogue must move beyond mere learning about other religions to the level of conversation among those who profess these differing religious traditions.

Grounded in our own faith tradition, rooted in our personal faith commitment, we are called to encounter other religious traditions. In this we imitate the example of the Lord that is presented in the Gospels: he shared his faith with the Samaritan woman while respecting her convictions; he praised the way the Samaritan cared for the dying man on the road; he responded to the Romans looking for answers to their needs.

True openness to the faith of others can lead us to questions that can cause considerable discomfort. At times, we may be tempted to retreat to the comfort of our own personal, private faiths as we have always known, permitting no further challenges; at other times we may be tempted to embrace a broad yet shallow tolerance that claims that truth is relative. Yet if we engage in serious conversation with people of other faith commitments, and engage in projects of social concern with them, we can often begin to experience our own faith more profoundly and more satisfyingly. What seemed to us as threatening challenges to our personal faith can become new windows of enlightenment to the possibilities of our faith and the faith of others in our world today.

The Society of Jesus, convened in 1995 as our thirty-fourth General Congregation, summed up this challenge in this way:

In the context of the divisive, exploitative and conflictual roles that religions, including Christianity, have played in history, dialogue seeks to develop the unifying and liberating potential of all religions, thus showing the relevance of religion for human well-being, justice and world peace. Above all we need to relate positively to believers of other religions because they are our neighbors; the common elements of our religions heritages and our human concern force us to establish ever closer ties based on universally accepted ethical values. To be religious today is to be interreligious in the sense that a positive relationship with believers of other faiths is a requirement in world of religious pluralism.

In encouraging you to seek some concrete modes for helping your students, your colleagues and your community as well as yourselves grapple with differences in faith traditions, let me suggest that the categories developed by the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue and Congregation for the Evangelization of People help organize your approach to the mission of Xavier University. The four dialogues recommended by the Church were incorporated into the Society of Jesus' way proceeding in 1995 in these words:

a. The dialogue of life, where people strive to live in an open and neighborly spirit, sharing their joys and sorrows, their human problems and preoccupations,

b. The dialogue of action, in which Christians and other collaborate for integral development and liberation of people,

c. The dialogue of religious experience, where persons, rooted in their own religious traditions, share their spiritual riches, for instance, with regard to prayer and contemplation, faith and ways of searching for God or the Absolute,

d. The dialogue of theological exchange, where specialists seek to deepen their understanding of their respective religious heritages, and to appreciate each other's spiritual values.

These four dialogues are already part of your way of being and acting at Xavier. I mention them as a way to help you reflect on what you are already doing so that you can consider how to organize and channel your energies in ever more effective ways, accomplishing your mission to educate the whole person. You, of course, are the best situated to organize and accomplish these dialogues, but clearly they are at the heart of what a university tries to do in its teaching, research and service. These dialogues take place in a particular place and time, within a unique culture. As you engage in these important dialogues of life, action, religious experience and theological exchange, it is important to keep in mind the profound impact that comes from the various cultures that situate Xavier.

From the days of Francis Xavier and Matteo Ricci to the time of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and the present, Jesuits have recognized the necessity of engaging cultures in their service of faith. Both appreciation and critique have characterized this engagement, gratefully acknowledging the goodness of human culture while rejecting whatever human customs are contrary to the revelation of the Gospel. Both remain essential today; and Xavier University, as Catholic and Jesuit, is well-situated to contribute to this dimension of the service of faith.

The Second Vatican Council encourages this combination of appreciation and critique in its document, The Church in the Modern World:

In every age, the church carries the responsibility of reading the signs of the times and of interpreting them in the light of the Gospel, if it is to carry out its task

Ours in a new age of history with profound and rapid changes spreading gradually to all corners of the earth. They are the products of people's intelligence and creative activity. A transformation of this kind brings with it the serious problems associated with any crisis of growth. Increase in power is now always accompanies by control of that power for the benefit of humanity.

Never before has the human race enjoyed such an abundance of wealth, resources and economic power; and yet a huge proportion of the world's citizens are still tormented by hunger and poverty, while countless numbers suffer from total illiteracy. Never before have people had so keen an understanding of freedom, yet at the same time new forms of social and psychological slavery make their appearance. Although the world of today has a very vivid awareness of its unity and of how one person depends on another in needful solidarity, it is most grievously turned into opposing camps by conflicting forces. For political, social, economic, racial, and ideological disputes still continue bitterly, and with them the peril of a war which would reduce everything to ashes.

The forty years that have passed since these insightful words were written have only intensified their depth, relevance and challenge.

At the Thirty-fourth General Congregation in 1995, the Society of Jesus emphasized both what is good in the world's cultures and the need for proper enculturation in the proclamation of the gospel: Our service of the Christian faith must never disrupt the best impulses of the culture in which we work, nor can it be an alien imposition from outside Our intuition is that the Gospel resonates with what is good in each culture. The Congregation acknowledged past mistakes by describing how Jesuits contributed to the alienation of the very people they wanted to serve and how Jesuits failed to discover the values, depth and transcendence of other cultures, which manifest the action of the Spirit. However, it refused to let past mistakes forestall future efforts. Rather, its document on culture addressed the problems just mentioned in the long quotation from the Church in the Modern World. The Congregation stated, The Gospel brings a prophetic challenge to every culture to remove all those things which inhibit the justice of the Kingdom.

Thus, it is important for all members of the university community to dialogue with one another about the cultural dimensions of your educational efforts in order to determine your response to the dominant culture of the United States. What are the best impulses of the American culture in which you work, the values, depth and transcendence? in your own culture, which manifest the action of the Lord's Spirit What are those things that inhibit the justice of the Kingdom of God from being manifested to all God's beloved daughters and sons. The same questions can be asked about various cultural entities that contribute to Xavier's life.

The cultural contexts and the importance of dialogue become obvious in discussing a topic like diversity. Many of our unexamined assumptions and biases become evident when we begin to consider the differences that exist among us. In recent years, I understand that much has been said about the need for gender diversity in your faculty, your administration and your student body. We should never forget that the first pages of the Bible show the Lord bringing diversity to his creation by distinguishing day and night, land and sea; as expression of God's richness, no one tree is the same as any other tree, no one animal a mere clone of another. In a very special way, each human person is called by its name. Unfortunately, instead of considering diversity as an expression of the infinite bounty of the Creator, we too easily use difference as a reason to hate one another. Color, gender, culture, and nationality as religion can be used to fight against one another. In the last pages of the Bible, all the differences contribute to building up the new City of God among us. Our task will be to integrate the diversities in the unifying vision of the Creator for his new heave and new earth. However, not all diversity, not all the differences come from the Creator, and these need to be overcome or eliminated. Gender and racial diversity should enrich humanity; but diversity in health condition is to be overcome; the diversity between good will and ill will should not be tolerated. The existence of great diversity in religion is a fact that is not always God-given, unlike gender and racial diversity.

As you evaluate your university's diversity, you might ask yourselves what you accomplish with your diversity, what end you expect to attain. You strive for diversity and celebrate it with your publicity when you achieve it. However, this is only the beginning of appreciating your diversity. What structures of dialogue would help promote serious conversations that might affect the very kind of women and men you are as teachers and as students? How can dialogue of life, action, religious experience and theological exchange assist and deepen your experience as educators so that you might admit and take advantage of ethical, racial, gender and religious differences among you?

How can you take greater advantage of the rich religious resources that form part of the cultural heritage of your city? As Xavier University sees itself as the meeting place for groups in the area concerned with racial and civic justice, how can this Catholic and Jesuit university see itself as the meeting place for the religions of the area? What greater claim could Xavier have for the service of faith that to have tapped religious diversity to engage in conversation intellectually, morally and spiritually!

The service of faith in Jesuit higher education, then, helps members of the university community develop a profound understanding of and commitment to their own religious tradition. This process necessarily includes openness to and learning from other religious traditions and appreciation and critique of culture. Religious diversity and cultural values are interdependent and overlapping not independent dimensions of our lives. Indeed, interreligious dialogue is one of the most powerful response to the global cultural malaise. It will take the cooperation of the world's religions to address adequately dehumanizing cultural forces.

Your system of Jesuit and Catholic higher education in the United States is, as you well know, a very expensive one, involving hundreds of millions of dollars, which you must constantly struggle to maintain. That high cost, however, can be seen as the price of your freedom to raise questions about God and faith and religion in a way no government-supported university in your country has the right to do. You have paid the price for 175 years. You continue and will continue to pay the price. Yet you must also ask yourselves how thoroughly and well you are using the freedom for dialogue and conversation you have purchased at such a great cost.

Your responsibility as educators is certainly to help your students to live and achieve success in an ever more globally oriented society. However, a Catholic and Jesuit university has the responsibility for even more: to prepare students to be leaders in this globally oriented society. We have seen in recent years that much of world politics and economy is rooted in religion but also how political and economic values can become pseudo-religions. Your students must be able to understand how faith in God lies at the heart of our motivation, our compassion, and our dedication. With dearly purchased freedom to carry on the conversation among men and women of faith, Xavier and the Jesuit universities in your country can be leaders in showing the relationship between faith and justice that leads humanity to the Holy City, the city ablaze with the glory of God, where the nations will walk in God's light.

To provide feedback, please email: jesuitresource@xavier.edu

Jesuitresource.org is developed by The Center for Mission and Identity at Xavier University with support from the Conway Institute for Jesuit Education. Learn more about Jesuit Resource.